Why Most American City Governments Aren’t Very Democratic

In American cities, political power is centralized in the hands of relatively small groups of professional politicians elected from big electoral districts consisting of tens of thousands – or even hundreds of thousands – of city residents.

The primary interest of a professional politician is that politician’s political career. It’s only natural. Most everyone makes their own career a priority.

To get elected and reelected, professional politicians must raise vast sums of money to run in their large populous districts. That money is typically donated by various business, labor or ideological interests.

But what about the interests of everyday people? Are they being served in America’s great cities?

Typical voter turnout in city elections in the United States hovers around a lowly 15%, suggesting that city residents feel powerless and disenfranchised.

It doesn’t have to be like this.

Political power can be democratized and decentralized. City governments need not be dominated by professional politicians. Many successful global cities are governed by everyday people, who keep their day jobs. It’s even possible to get the controlling influence of money out of city politics.

At Cities Rising, we are committed to educating the residents of America’s cities about how they can reform their city charters to empower everyday people and significantly improve urban democracy.

City Councils

The essential solution to making our city governments more representative of the people is to significantly increase the size of city councils while significantly decreasing the size of the political districts from which city councilors are elected.

Other democratic reforms may be desirable, or even necessary, but city councils are the lynchpins of the whole system (see below under strategies).

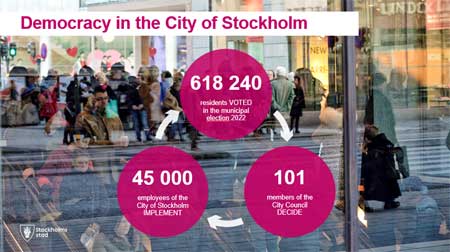

Most Americans will be surprised to learn that many successful global cities are run not so much by professional politicians but by urban legislatures comprised of numerous everyday citizens. For examples, the governing bodies of Stockholm, Sweden, Zurich Switzerland and Cape Town, South Africa have 101,125 and 230 members, respectively.

In the United States, where money in politics is a severe problem, we can radically reduce the cost of elections by reducing electoral districts to the size of neighborhoods, where city residents could elect their representatives based on relationships and reputations instead of money and marketing. The key is to make these electoral districts sufficiently small.

Small districts mean large city councils or city legislatures. The usual criticism of large governing bodies is that they are “unwieldy,” but the examples above show that this is not necessarily the case. In fact, large assemblies of elected officials potentially make government more efficient by bringing to bear the diverse range of professional and life experiences found within a city’s population.

The work of legislation is done within committees and a large governing body permits the creation of numerous specialized committees that can efficiently focus attention on a wide range of community challenges.

Citizen Representatives or Professional Politicians?

Many years of public opinion survey data reveals that everyday citizens lack confidence in professional politicians.

The experience of successful cities outside of the United States proves that everyday people can effectively and democratically oversee their own city governments while keeping their day jobs.

It may be desirable to pay the leadership of elected governing bodies for full-time work, but ultimately all major legislative decisions can safely be made by an elected body of public-spirited but otherwise normal citizens working part time for modest financial compensation.

Part-time pay for elected officials is appropriate but might be determined through a mechanism other than by the elected officials themselves. Compensation could be tied to the minimum wage or set by a citizen jury (see below).

Mayors and Executive Councils

Currently, the powers of American mayors vary from city to city. In some cases, the mayor is little more than a spokesperson for the city council, sometimes a mayor is tasked with overseeing a professional city manager, and some mayors possess powers like that of a CEO, who largely establishes and carries out the city’s agenda.

Precisely how powerful a mayor should be, and to whom that mayor should be beholden, are essential considerations when thinking about city government.

All American big-city mayors hold offices for which they must first raise hundreds of thousands of dollars, or even millions of dollars, in campaign donations to win them. Such political fundraising is harmful to the public interest for at least three reasons.

First, an accomplished citizen who would otherwise make an excellent mayor might be dissuaded from running for office because of the heavy fundraising burden.

Second, the skills and motivations that make someone a good fundraiser might not make that same person the most ethical or competent public servant.

Third, and most significantly, a mayor deeply indebted to business interests or public unions may not always prioritize the needs of city residents once elected.

All of this is deeply problematic.

Some successful cities outside of the United States take an entirely different approach. The city of Stockholm, Sweden, offers a particularly bold contrast.

In Stockholm, the 101-member city parliament (who again are everyday citizens and not professional politicians) chooses the mayor along with 10 other (this number can vary) executive councilors. The consequences of this system compared to American city government models is profound.

First, the mayor doesn’t have to raise any campaign money. That huge potential source of corruption in American city elections is almost completely absent from the Stockholm model.

Second, because the mayor and executive branch are chosen by the city’s citizen-based city parliament, they are effectively hired by the parliament to carry out its will. Therefore, the city parliament is where the city agenda is set, not in the mayor’s office. Such an arrangement is in keeping with classical political theory, where one political branch, a legislature, makes all the policy and budgetary decisions, and another, the executive, carries out those decisions. Systems that mix legislative and executive powers should probably be avoided and those that do are invitations to corruption.

Third, distributing power in a divided executive branch has consequences. The mayor, in such a system, is sometimes referred to as “the first among equals.” In Stockholm, the mayor’s role is to run executive council meetings, oversee the finance committee, and serve as a figurehead for the city. Each of the other councilors oversees a specific city department. The system, therefore, encourages specialized democratic oversight over each city department, which ideally helps maintain government efficiency. And the divided executive branch is probably a disincentive to the abuse of power.

Swiss cities offer a slightly contrasting model. Zurich, for example, is governed through a citizen-based part-time city parliament of 125 members with a large executive council much like Stockholm’s, except that the mayor and executive council are elected directly by the people and run at-at large.

German cities feature government by similarly large democratic citizen assemblies but utilize strong CEO-style mayors, also elected at-large.

City Officers

In many American cities, municipal officers like the city attorney (sometimes called the “attorney general”) or the city auditor, are elected by the people at large. These are not supposed to be policy-making positions, yet candidates, especially city attorneys, campaign as if they are. City attorneys are not empowered to make the law; they are supposed to fairly enforce the law. Partisan politics and gratitude for certain campaign contributions can easily cause conflicts of interest.

At the same time, voters are usually ill-equipped to select the best candidate for a city attorney or auditor, assuming the best candidate ever appears on a ballot. Voters can’t review resumes in the voting booth nor interview applicants, as would be done in a normal hiring process.

Therefore, as city councils become more democratic, it may make sense to empower these elected bodies to appoint the city’s officers, rather than make city offices subject to popular election. A legislative body can engage in a more normal hiring process, by reviewing the resumes of applicants and conducting interviews. And once appointed, city officers can serve at the pleasure of the elected officials who appoint them and oversee their work.

More innovatively, a city might try picking its officers through a citizen jury process, which would decrease the possibility that these offices are filled through patronage. (See Citizen Juries below)

Proximity of Government to the People

The first article of the Berlin, Germany, city charter guarantees the distribution of power throughout that large city in the form of subsidiary democratic bodies, in effect miniatures of the city’s main parliament in each of Berlin’s boroughs.

Here is an idea, not ever employed nor hardly considered, for America’s largest cities. In the case of New York City, each borough is in fact an entire county, or a city unto itself in terms of size, yet none has its own democratic government.

If one were to sit down and rationally design a democratic government for America’s largest city, wouldn’t it be reasonable to first ask what powers and resources might be decentralized to promote democratic self-rule and efficiency? Shouldn’t we want to bring democratic government closer to the people it is supposed to serve?

An Innovative Approach: Citizen Juries

The jury of fellow citizens is among the most trusted democratic institutions, going back hundreds of years. In court cases, we regularly rely on juries in matters of life and death.

What if some public policy decisions were made by juries? It’s starting to happen all over the democratic world, with relatively large juries randomly selected but with political and demographic characteristics that make the jury an accurate reflection of the city as a whole.

Possibly the most appropriate place to call juries of citizens to decide public policy issues is in situations where elected officials have inherent conflicts of interests.

For example, should an elected body have the authority to decide its own financial compensation? Probably not. Here is a task well suited to a citizen jury.

For another example, a citizen jury could be a check against corruption. Perhaps citizen juries could approve all major hiring decisions, to ensure that no patronage or graft is involved in the city’s business.

A Citizen Jury could hire the City Clerk. Distrust of elections is probably higher now than at any time in memory. Should the official in charge of elections really be potentially a partisan creature, dependent on elections for his or her own appointment? It would almost surely be better for a jury representing all the political interest within a community to choose the City Clerk via consensus or something close to it.

Finally, it must be acknowledged that the kind of relationship-based democracy desired by creating small, community-sized, electoral districts (described above), is not necessarily easy in urban neighborhoods, often consisting of tall apartment buildings, where a sense of community can be elusive, and where relationship-building and door-to-door campaigning is a challenge. Might citizen juries actually be the best way to make democratic decisions? Could small-district democratic representation and citizen juries be blended into a new kind of new bicameral system? What if every city budget or tax rate increase required the approval of a citizen jury?

There are probably two essential challenges when considering the efficacy of a citizen jury. First, the jury must be truly representative of the population at large. Second, the jury must be fairly exposed to all sides of any question it must decide. Failure to achieve either of these objectives could fatally defeat a jury-driven decision-making process.

Because an expanded role for citizen juries is such a promising prospect, it’s critical that the potential pitfalls are thoroughly understood and addressed before systematic implementation, lest the concept be discredited before it has a real chance to succeed.

Citizens’ Initiatives and City Charter Reform Strategies

The ability of ordinary citizens to reform their own city governments varies by city and particularly by state. Wholescale revision of city charters without the heavy hand of self-interested professional politicians is usually impossible. Typically, a city charter cannot be rewritten except through the appointment of a charter commission, which is almost always chosen by the city council. It can be seen as a case of the foxes proposing a redesign of the hen house.

But happily, the first progressives who gave us our existing small city councils were at least wise enough to permit the people, themselves, to amend their city charters without the participation of sitting politicians.

Costs for even a single charter amendment can be high. It’s a shame that the practice of a process designed to keep government in the hands of the people now comes down to money (and in some cities, a big sum of money). In most cases, the onerous task of collecting enough signatures in the requisite space of time necessitates the hiring of paid signature gatherers. (If the goal were to make the process democratic and rigorous but not financially costly, then we would use systems of electronic signature gathering, as they do in as they are starting to do in Europe.)

Nevertheless, the key point is that in almost every city, the people themselves can amend their city charter without relying on the approval of sitting politicians. This means that change via direct action of the people, with some financial support, is possible at the city level almost everywhere.

In addition to cities, the same is true for most counties. In some places, county government effectively has the same responsibilities as city government, with identical challenges and possibilities, including the possibility of amending county charters through citizens’ initiatives.

Amendments are, by their nature, surgical. Hopefully by now it’s clear that there are many good ideas that could make American city government more democratic and probably more efficient. But which reform should be prioritized?

If the goal is a wholescale review and reform of the city charter, which is likely necessary in every American city given that the fundamental structures have largely been frozen in place for more than a century, then the most important reform is the radical expansion of city councils. New city councils, comprised of members unconcerned with political careers, will likely be more inclined to appoint city charter commissions that prioritize democracy. Open-minded charter commissions might be willing to effectively start again, with a blank piece of paper and a desire to ensure city government that is of, by and for the people.

How Cities Rising Can Help You Make Your City More Democratic

We at Cities Rising hope you will consider taking the lead in reforming your city government to make it more democratic.

We are here to help. We are happy to provide free consultation, including consultation with elected officials serving the people of foreign cities operating under the successful democratic governing structures described here.

Let’s start a conversation to make your city or county much more democratic!

Please Contact us at: stephen@citiesrising.org

Learn more about Cities Rising founder, Stephen Erickson.